Jewish Farmers July 24, 2014

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Ecozoic, Eden Village Camp, environmentalism, Jewish spirituality, meditation, Rabbi Jeff Roth, Vegetarianism/veganism.add a comment

A recent article in the New York Times “New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm” spotlights some of my favoriate organizations in the Jewish social justice, environmentalism and spirituality movement. Pluralistic and conscious of differences of all sorts, it gives hope to me as a Jew during this difficult time. In particular I am proud to say that I’ve volunteered for three years at Eden Village Camp (mentioned in the article)

(Teaching Science at Eden Village, July 2011, photo by Meg Stewart)

and taken my Vassar students to Kibbutz Ketura on our March 2014 study trip. Note that althought Kibbutz Ketura is up to some interesting work, we also visited Kibbutz Lotan where there is some very interesting work going on in earth building and permaculture.

(Making bricks at Kibbutz Lotan)

I’ve also visited the Israel School of Herbal Medicine and spoken to rabbinical students on retreat at the Isabella Freedman retreat center. But i’d also like to add that the Institute for Jewish Spirituality, though not connected explicitly with Jewish agriculature and sustainability has been a thought leader in encouraging pluralism and spirituality among Jews. It’s an organization not to be missed. And I’ll also add the fact that I hope that in the future, students will come to Vassar as students to learn about Jewish environmentalism through our Jewish Studies and Earth Science programs with field work opportunities on the Vassar farm it’s CSA, the Poughkeepsie Farm Project, as well as nearby Eden Village Camp! Finally, a salute to Rabbi Jeff Roth who has been ahead of the curve on all of this. Check out his Awakened Heart Project!

Not Standing Still: A Solstice-time Reflection from a “Geologian” December 21, 2012

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in contemplative practice, Ecozoic, environmentalism, geologian, meditation, mindfulness practice, science, Thomas Berry.Tags: environment, liberal arts college, lotus position, science

add a comment

This piece appears on the Shambhala SunSpace blog.

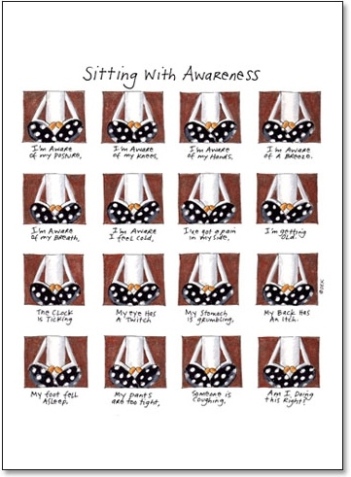

Among my favorite cartoons is one my mom gave me by the cartoonist and author of The Soul Support Book, Deb Koffman. Entitled “Sitting with Awareness,” in each of sixteen small square frames Koffman depicts a person sitting in lotus position wearing, what we call in my house “at–homes”– in other words sweatpants. (Click here to visit Koffman’s site — you’ll find the image under “Mindfulness Prints.”) Phrases beneath each frame taken together constitute the following poem. I sure can relate to it, and maybe you can too:

I’m aware of my posture, I’m aware of my knees, I’m aware of my hands, I’m aware of a breeze.

I’m aware of my breath, I’m aware I feel cold, I’ve got a pain in my side, I’m getting old.

The clock is ticking, my eye has a twitch, my stomach is grumbling, my back has an itch.

My foot fell asleep, my pants are too tight, someone is coughing, am I doing this right?

Why do I relate to this poem? Because as I pursue my work as a geoscientist–educator at a liberal arts college — reading, teaching, and striving at the intersections of earth science, gender studies, environmental studies, and history of science — I often wonder, “Am I doing this right?”

In answer to that question, I’m encouraged by news that The University of Virginia received a multimillion dollar gift this year to establish a Contemplative Sciences Center. One purpose of the center will be to promote awareness about the potential benefits of training one’s mind and body. David Germano, a professor of religious studies in the College of Arts and Sciences who will help lead the center commented, ”Hopefully, like drops in the ocean, this training can lead people to greater reflexivity, greater understanding, greater caring, greater efficiency and greater insight.” Huzzah to that.

This means greater validation for the kind of work I try to do as a contemplative educator in my science classes. Not that I doubt the benefits of contemplative practices in higher education. Students continue to write to me post-graduation, amidst real-life struggles about how the contemplative approaches I’ve taught them while they were in college have been among the most sustaining practices they’ve used to deal with everyday living. It’s just that professional scientific societies offer much advice about the fact that geoscientists — as educators and Eaarthlings — must involve ourselves in addressing “critical needs for the 21st century.”

For example, we are urged to prioritize efforts to ensure reliable energy supplies in an increasingly carbon-constrained world; provide sufficient supplies of water; sustain oceans, atmosphere, and space resources; manage waste to maintain a healthy environment; mitigate risk and build resilience from natural and human-made hazards; improve and build needed infrastructure that couples with and uses Earth resources while integrating new technologies; ensure reliable supplies of raw materials; inform the public and train the geosciences workforce to understand Earth processes and address these critical needs. It’s a long and lofty list.

But critically absent from the “critical needs” list are endeavors equally critical to achieving this balance on Earth. For example, for my personal list of critical needs as a science educator, I’ve added the following imperatives:

- Tell a scientific story of the universe that has a mythic, narrative dimension that elevates the story from a prosaic study of data to an inspiring spiritual vision;

- Articulate our dream of the future Ecozoic era, defined as that time when humans will be present to the Earth in a mutually enhancing manner;

- Circumvent the problem of anthropocentrism that is at the center of the devastation we are experiencing;

- Allow acknowledgment that currently, human beings are a devastating presence on the planet; supposedly acting for our own benefit, truthfully we are ruining the conditions for our health and survival as well as that of other living beings;

- Promote hope through contemplation of how tragic moments of disintegration over the past centuries were followed by hugely creative moments of regeneration;

- Recover the capacity for subjective communion with the Earth and identification with the cosmic-Earth-human process as a new mode of interdependence;

- Nourish awareness for a vision of Earth-human development that will allow a sustainable dynamic of the modern world;

- Foster development of intimacy with the natural world.

I developed this list as a result of reading the work of Thomas Berry (1914-2009), a leading scholar, cultural historian, and Catholic priest who spent fifty years writing about our relationship with the Earth. “The universe,” he said, “is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.” Berry, had a doctorate in history from The Catholic University of America, studied Chinese language and Chinese culture in China and learned Sanskrit for the study of India and the traditions of religion in India. One of his earliest books was a history of Buddhism. Having established the History of Religions program at Fordham University Berry published numerous prophetic books including The Dream of the Earth, The Great Work, and his last work The Sacred Universe: Earth, Spirituality, and Religion in the Twenty-First Century. This last writing especially fuels my conviction that science done well is also a spritual discipline. Berry called himself a “geologian” and wrote:

Our new acquaintance with the universe as an irreversible developmental process can be considered the most significant religious, spiritual, and scientific event since the emergence of the more complex civilizations some five thousand years ago…. if interpreted properly, the scientific venture could even be one of the most significant spiritual disciplines of these times. This task is particularly urgent, since our new mode of understanding is so powerful in its consequences for the very structure of the planet Earth. We must respond to its deepest spiritual content or else submit to the devastation that is before us (The Sacred Universe 119-120).

The notion that that my geology may be at once both scientific and spiritual has me also adopting the moniker, “geologian.” And that the University of Virginia is moving forward with its Contemplative Sciences Center fuels my hope that engaging science as a spiritual discipline in order to encourage embodied paths to wisdom and social transformation is in itself a worthwhile practice.

We’ve almost arrived at the winter solstice here in the northern hemisphere. On the year’s shortest day, the sun appears to halt in its progressive journey across the sky. From Earth it seems that the sun hardly changes its position on this day, hence the name solstice meaning ”sun stands still.” But despite appearances, the sun is changing its position relative to the Earth inasmuch as, speaking scientifically, the Earth circles the sun each year while it rotates on a tilted axis and creates the changing seasons (the hemisphere that faces the sun receives longer and more powerful exposure to sunlight). For half of each year the North Pole is tilted away from the sun and on the winter solstice the tilt makes the sun seem most faraway. This astronomical event announces the onset of winter in the northern hemisphere.

Speaking as a “geologian” I observe that these are indeed the darkest days of the year. But as I pause, as the sun seems to, at this point in my yearly journey around the sun, I note that in the darkness is the promise of the gradual return of more light. As you circle the sun and participate in the turning of the wheel of the year, what do you notice and to what do you bow?

Citizen-Scientist and Meditator November 16, 2012

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in contemplative practice, meditation, mindfulness practice, science.add a comment

A recent Scientific American article reports on a new study published in Annals of Family Medicine that found that adults who practiced mindful meditation or moderately intense exercise for eight weeks suffered less from seasonal ailments during the following winter than those who did not meditate or exercise.

A recent Scientific American article reports on a new study published in Annals of Family Medicine that found that adults who practiced mindful meditation or moderately intense exercise for eight weeks suffered less from seasonal ailments during the following winter than those who did not meditate or exercise.

Participants who had meditated missed 76 percent fewer days of work from September through May than did the control subjects while those who had exercised missed 48 percent fewer days during this period. The severity of respiratory ailments also differed between the two groups. Those who had meditated or exercised suffered for an average of five days while the colds of people in the control group lasted eight. According to Scientific American, lab tests confirmed that the self-reported length of colds correlated with the amounts of antibodies in the body, something considered to be a biomarker for the presence of a virus.

I’m not surprised by this report. But I am taken by the fact that, once again, your average meditating Jo, is supposed to feel validated by the fact that science confirms what she already knows to be true. That we have been forced to wait for scientists to confirm observations that are obvious, such as the fact that water that omits odors is contaminated with toxic chemicals has gotten us human beings into quite a few predicaments. I need to look no further than the Hudson valley where I live as the U.S. EPA stops for this season it’s dredging of Hudson River sediments long contaminated with PCBs.

As a person who sits 30-minutes daily, I know that I am quite aware of what is going on with my body. This is not news to anyone who has a regular sitting practice. Thus, when I read the Scientific American report of the study of meditators and those who exercise regularly, I hardly thought it was news. An intuitive explanation for the fact that those who meditated or exercised suffered for a shorter period of time the colds or flus they contracted is easily explained as follows. A person who meditates is much more likely than one who does not to note the fact that she is feeling unwell; such a person then has the opportunity to choose to take the time for rest and renewal and thus shorten the period of illness. This is common sense.

I have no complaint with looking to science for confirmation of reality but I think we need not depend on it to the exclusion of one’s own basic powers of observations, which are of course enhanced by mindfulness practice.

Taking the Practice Seriously June 19, 2012

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Buddhist practice, meditation, mindfulness practice, monastery, Thomas Berry, Vassar College.add a comment

This piece is cross-posted on Shambhala SunSpace.

Shambhala SunSpace blogger Jill S. Schneiderman noticed an interesting article in the New York Times yesterday. And she wasn’t the only one; James Atlas’ “Buddhists’ Delight” is currently the most-emailed story on the Times site. (And interestingly enough, the Washington Post published an American-Buddhism piece yesterday, too.) Here Schneiderman responds to Atlas’s piece.

.

Tengboche Buddhist monastery, Nepal (via Creative Commons)

Yesterday I read “Buddhists’ Delight,” an opinion piece in the Sunday New York Timesby James Atlas, a long-time literary journalist who has written for the New Yorker and published a biography of Saul Bellow. In the piece Atlas describes four days he spent at a Buddhist meditation center “in retreat, from a frenetic Manhattan life.” It’s obvious from the essay that Atlas brought “beginner’s mind” to the retreat and his report of this first encounter with Buddhist meditation is pretty insightful. Atlas’ piece is a good introduction to the experience and I intend to give it to friends who are contemplating the possibility of sitting a multi-day retreat. Nonetheless, as experienced meditators know, there’s more to meditation than beginners may realize.

So although it’s a bit outside my usual bailiwick of earth science and dharma, I wanted to add to Atlas’ observations from my position as a professional educator who is convinced that the practice of meditation is not only powerful but crucial to the rehabilitation of a society and planet in critically ill condition. Atlas recognizes that meditation is an important tool for individuals trying to cope with the insane state of our world; he even notes the heft of Engaged Buddhism.

While sitting this morning I heard the carillon ring the early morning hour and I felt grateful, as I always do, to the monastic traditions that created the institution of the Monastery, the precursor to the modern University. Though most universities today have lost the spiritual dimension that once accompanied the educational mission of the Monastery, as an educator today, I aspire to reclaim the spiritual as a legitimate dimension of higher education.

As a regular practitioner and frequent retreatant at the Garrison Institute, I have experienced the transformational power of meditation that Atlas reports having sensed while he was on retreat in Vermont. Though as a beginner in the practice he may not realize it, Atlas has tapped into what multitudes of more experienced meditators know: meditation transforms minds and lives.

In “The University” a chapter in his book The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future, ecotheologian Thomas Berry admonishes readers that universities should “reorient the human community toward a greater awareness that the human exists, survives, and becomes whole only within the single great community of the planet Earth. “ The bells ringing in the carillon of the Vassar College Chapel every hour remind me of this; the bells validate my impulse to teach meditation as a tool for societal rehabilitation.

Oxygen in My Bones May 22, 2011

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Buddhist practice, earth system science, hydrosphere, Jewish spirituality, meditation, mindfulness practice, science, Sylvia Boorstein.add a comment

This piece is cross-posted on Shambhala SunSpace.

In his book A Path With Heart Jack Kornfield asserted that great spiritual traditions “are used as means to ripen us, to bring us face to face with our life, and to help us to see in a new way by developing a stillness of mind and a strength of heart.” Having just returned from a seven-day mindfulness retreat with the two dozen or so other contemplatives in my Institute for Jewish Spirituality-sponsored Jewish Mindfulness Teacher Training cohort, Kornfield’s statement resonates for me. Seeing in a new way requires that I continue to cultivate what Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel called “radical amazement,”—a heart-strengthening feeling of awe and connection.

In his book A Path With Heart Jack Kornfield asserted that great spiritual traditions “are used as means to ripen us, to bring us face to face with our life, and to help us to see in a new way by developing a stillness of mind and a strength of heart.” Having just returned from a seven-day mindfulness retreat with the two dozen or so other contemplatives in my Institute for Jewish Spirituality-sponsored Jewish Mindfulness Teacher Training cohort, Kornfield’s statement resonates for me. Seeing in a new way requires that I continue to cultivate what Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel called “radical amazement,”—a heart-strengthening feeling of awe and connection.

Amidst the daily activities familiar to all mindfulness practitioners—walk-sit-walk-sit-walk-sit-eat-walk-sit-walk-sit…— retreatants led three prayer services: sharacharit, mincha, maariv and an afternoon teaching. The services were atypical in that they involved only a brief introduction to each prayer, group chanting, and then silence. In the course of the week, each individual offered a teaching on an assigned subject. My assignment, scheduled for Shabbat afternoon, was instructions for breathing.

Now I have to admit, having received the assignment, initially I hoped it would simply go away! I wondered what I, a geoscientist, could offer this experienced group of spiritual practitioners by way of breath instructions. We had already been sitting for days together concentrating on the breath. Donald Rothberg’s humorous quip at a previous retreat kept coming up: breathing through the mouth is like trying to eat spaghetti through the nose! Fortunately, I found a possible answer in a teaching by Rabbi Jeff Roth during an evening dharma talk.

Jeff instructed each of us to “teach our own Torah”—in other words, our own truth—so I resolved to teach mine: the Torah of the Earth System.

At first I was intimidated because for “the people of the book” the Torah itself is the quintessential text, the most worthy object of scrutiny. But since my Torah is the Earth, I feared being perceived as a bit dim. “Dull as a rock” resounded in my head. Fortunately I was able to acknowledge the hindrance of doubt and pressed onward. Using Sylvia Boorstein’s metta phrases in order to soothe myself —may I feel safe, may I feel content, may I feel strong, may I live with ease—I offered to the group my teaching, breath instructions for cultivating radical amazement, breath instructions that emphasize our connections to the Earth as a living system.

We geoscientists think of the Earth as a system of four interacting spheres, approximately from the inside outward: geosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and atmosphere. Humans and other mammals are obviously connected to the atmosphere through our inhalation of oxygen and exhalation of carbon dioxide. Our respiration also connects us to trees because they essentially inhale carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen. And human bodies as a whole contain up to 60 % water. So as embodied beings we are intimately interconnected with atmosphere, biosphere, and hydropshere. What may be less obvious is that we are linked closely with the geosphere. Our teeth and bones, parts of living beings that readily fossilize, are composed of hydroxyapatite, a carbonate mineral made of the elements calcium, phosphorus, oxygen, and hydrogen. The very air we breathe and the water we drink has been incorporated into our skeletal framework and gets preserved in the fossil record!

I find it remarkable that isotope geochemists can analyze the ratio of heavy and light oxygen isotopes (O-18 and O-16) in the bones and teeth of fossilized organisms and identify the environments in which they lived. Since teeth and bone form in a relatively narrow window of time, the oxygen isotope composition inherited from drinking water taken into the body of a living being gets locked into the hydroxyapatite. Using the distinctive oxygen isotopic signatures of water in different environments, some investigators have been able to determine the habitats and migration patterns of extinct organisms. What is the oxygen isotopic signature of my bones? What is the past history of the oxygen that in part forms the skeleton that makes up the body that I inhabit?

So with my cohort we sat: breathing in may I feel connected to the atmosphere; breathing out may I feel connected to the hydrosphere; breathing in may I feel connected to the geosphere; breathing out may I feel connected to all beings of the biosphere. Stilling our minds with this breathing practice, together we undertook the project of cultivating radical amazement.

Radioactivity, science, and spirit March 31, 2011

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in book review, Buddhist practice, contemplative practice, disasters, earth community, Japan, meditation, radioactivity, science, Tsunamis.add a comment

This piece is cross-posted at Shambhala SunSpace and at Being.

Radioactivity. Life. Death. These are front-and-center in my thoughts these days as I contemplate the fallout from the nuclear plant meltdown generated by power outages, triggered by a tsunami, set off by an earthquake in Japan. Amidst these events, I turned my attention to reading Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie, A Tale of Love and Fallout by Lauren Redniss.

Currently, the book is on exhibit at the New York Public Library. The author, an artist, teaches documentary, drawing, graphic novels, and printmaking at the Parsons School of Design, so one might be excused from not immediately recognizing the logic of her having written a book on the Curies (who shared with Henri Becquerel the1903 Nobel Prize in physics for their research on radiation.) But there’s little that is logical about the way this story reveals itself and that’s what makes it beautiful and such a pleasure to read. The book is a piece of art composed of images and words. Although told in roughly chronological fashion, mostly the story has long tendrils of other tales. In this regard as well as others, I suspect it will be of interest to people fascinated by the intersections of science and mind.

Here’s what I liked about it. To me, the format ofRadioactive mimics the way a mind—mine at least–works. All of us dedicated to a regular sitting practice know that just a few breaths into a sit, the mind is likely to take an excursion, follow an idea. After some time we wake up to the fact of our distraction and come back to focusing on the breath. It is in this manner that the story of the Curies, their colleagues, friends, enemies, lovers, and offspring unfolds. Unlike histories of science or biographies of scientists that are so often linear and wordy, this one provides multiple pursuable pathways.

Here’s what I liked about it. To me, the format ofRadioactive mimics the way a mind—mine at least–works. All of us dedicated to a regular sitting practice know that just a few breaths into a sit, the mind is likely to take an excursion, follow an idea. After some time we wake up to the fact of our distraction and come back to focusing on the breath. It is in this manner that the story of the Curies, their colleagues, friends, enemies, lovers, and offspring unfolds. Unlike histories of science or biographies of scientists that are so often linear and wordy, this one provides multiple pursuable pathways.

Even if they know little else, most people know that Marie Skłodowska Curie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize. They may also know that her first Nobel in physics was followed by a second in 1911 in chemistry for the discovery of the elements radium and polonium. But the story of Marie and Pierre Curie is much more interesting than that plain fact. It involves a stimulating partnership of spouses engaged by the same scientific questions; infatuation with the invisible; Marie’s scandalous love affair after her husband’s accidental death by horse-drawn carriage; an ongoing commitment to scientific and medical investigations that ultimately killed her, and offspring—both biological and scientific—who have carried on their work. And in Radioactive, entwined images and prose create a fabric that relates the stories of the Curies to more modern-day concerns: Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and two World Wars. Redniss indulges her readers with haunting cyanotype and archival images offered up in nonlinear fashion; this is a boon for right-brainers such as I whose minds tend toward wandering.

A most fascinating facet of the book tells of the Curie’s explorations in Spiritualism—a movement that suggested the possibility of contact with the divine. As Redniss tells it:

Electricity, radio, the telegraph, the X-ray, and now, radioactivity—at the turn of the twentieth century a series of invisible forces were radically transforming daily life. These advances were dazzling and disorienting: for some, they blurred the boundary between science and magic….Spiritualists claimed that clairvoyants possessed “X-gazes,” and that photographic plates placed on the forehead could record vital forces of the brain, or “V-rays.”

The Curies and their circle—including leading artists, writers, and scientists such as Edvard Munch, Arthur Conan Doyle, Henri Poincare, Alexander Graham Bell—participated in the Spiritualist séances of Italian medium Eusapia Palladino and considered it possible to find in spiritualism the origin of unknown energy that might relate to radioactivity. In fact, as Susan Quinn recounts in Marie Curie: A Life, just prior to his death Pierre Curie wrote to physicist Louis Georges Gouy about his last séance with Palladino “There is here, in my opinion, a whole domain of entirely new facts and physical states in space of which we have no conception.”

Both scientists and spiritualists believed that there was much that exists in the world that cannot be seen by the naked eyes of humans.

Radioactive is a story of mystery and magic as well as a history of science and invention. It shows how science, so often thought of as motivated by passionate rationality, is equally about marvelous ambiguity. The Curies, perhaps influenced by their encounters with spiritualism, devoted their lives to the search for evidence of phenomena they could not see but that they believed existed. The implications of what they found—the good and the bad, medical innovation and nuclear proliferation—they couldn’t fully anticipate.

A recent New York Times article about nuclear energy, “Preparing for Everything, Except the Unknown,” states the obvious: experts say it is impossible to prepare for everything. As a mindfulness practitioner I’d like to offer a corollary to that statement: when we sit seemingly doing nothing, plenty happens—we don’t see it, but we sense it. Redniss’s history of the lives of Marie and Pierre Curie inspires me as a scientist to continue to pursue my mindfulness practice.

Trackbacks are closed, but you can post a comment.

Benefits of Meditation Practice February 2, 2011

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in contemplative practice, meditation.add a comment

Thanks to my friend and former student, Beth Feingold, for calling my attention to this piece from the January 28, 2011 New York Times. I heard Dr. Hölzel speak at a contemplative curriculum conference sponsored by the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society at Smith College in August 2009 and found her research fascinating. I have experienced the benefits from my sitting practice that are described in this Times article.

Thanks to my friend and former student, Beth Feingold, for calling my attention to this piece from the January 28, 2011 New York Times. I heard Dr. Hölzel speak at a contemplative curriculum conference sponsored by the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society at Smith College in August 2009 and found her research fascinating. I have experienced the benefits from my sitting practice that are described in this Times article.

Letting Go of Mental Formations — Images from Geophysical Fluid Dynamics December 27, 2010

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Buddhist concepts, Buddhist practice, fluid flow, meditation, Sylvia Boorstein.add a comment

This piece is cross-posted at Shambhala SunSpace.

For some people, this time of year offers especially good opportunities to practice the Buddhist art of letting go of mental formations—our conditioned responses to the objects of experience. Whether waiting in line at an airport, inching along in a traffic jam, sharing a festive meal, or sitting quietly alone, one’s mind lunges towards distractions on familiar themes.

The challenge is, of course, to awaken to the moment, release that pattern of thought, and return to the present. I’d like to suggest the visualization of a geophysical process that may help in this endeavor.

The thought came to me in that semi-conscious, pre-awake state, just before the early morning bell at a recent silent retreat; a picture of fluid flow manifested in my consciousness. Later in the day on the cushion, I put it to use. I pictured the transition from laminar to turbulent flow in a fluid medium. Allow me to explain.

Laminar flow, also known as streamline flow, occurs when a liquid or gaseous fluid flows in parallel layers with no disruption between them. It’s the opposite of turbulent flow which is a fluid regime characterized by chaotic particle motion. In the simplest terms, laminar flow is smooth while turbulent flow is rough. In turbulent flow, eddies and wakes make the flow unpredictable. You can see it in the cascade of water over rocks…

….or in the upward flow of a plume of smoke.

We sedimentologists ponder “flow regimes,” from laminar through transitional (a mixture of laminar and turbulent flow) to turbulent, because they affect the erosion, transport, and deposition of rock particles, large and small, from one environment to another. They bear on the magnitude of devastation associated with floodwaters and debris flows like those brought on by recent rainstorms in California.

Turbulent fluid flow with its high velocity moves material in apparently random, haphazard motion. Upwelling, swirling eddies entrain sediment and keep it moving not only along the fluid but also up and down within it. Most natural fluid flow is turbulent like the motion of broad, deep, fast moving rivers. Only very slowly moving fluids—think maple syrup or asphalt–exhibit laminar flow. Although laminar flow can help transport material down current it moves material less effectively than turbulent flow because it lacks the ability to keep particles of sediment lifted up in the moving current.

And here’s where the business of letting go of mental formations enters the picture. On the mat, “by and by” as Buddhist teacher Sylvia Boorstein likes to say, my mind drifts away from the breath to a thought, and the thought begins to lead me far away from my cushion and my focused attention on the breath. But I’m more able to let go of those mental formations when I picture them flowing away. They are my streams of thought, literally. And I feel them move away from my body, first in laminar fashion and ultimately dispersing into the turbulent flow regime where they scatter in eddies and swirls.

Jill S. Schneiderman is Professor of Earth Science at Vassar College and the editor of and contributor to For the Rock Record: Geologists on Intelligent Design (University of California Press, 2009) and The Earth Around Us: Maintaining a Livable Planet (Westview Press, 2003).

For more “Earth Dharma” from Jill S. Schneiderman, click here.

See also our Shambhala Sun Spotlight on Buddhism and Green Living.

Breathing With Dolphins August 14, 2010

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in BP/Deepwater Horizon oil catastrophe, Buddhist concepts, Carl Safina, disasters, earth community, fossil fuel, meditation, ocean pollution, oil, oil spill.3 comments

This piece is cross-posted at Shambhala SunSpace

During August, for my Institute for Jewish Spirituality Meditation Teacher Training program, we were to focus on breathing. During the first week of the month our teachers directed us to get back to basics—to use the breath actively as a concentration practice, experimenting with techniques such as labeling, counting, and paying attention to specifics such as beginning, middle and end; long, short, rough, and smooth.

We should set the intention to let the breath saturate our experience—to invite whatever pleasure arose, to grow and be sustained. We were to utilize this exercise to explore ways of deepening concentration. During the second week we worked with a sense of receiving the breathing and letting the attention be more on the whole body. I had hoped to establish mindfulness of the body so that the breath would simply come to me.

I dedicated myself to breathing in this receptive way, but I had trouble. My attention kept getting pulled to a recollection of a recent TED talk by Carl Safina about “clean-up” efforts related to the BP Gulf of Mexico oil gusher. Dr. Safina — an ornithologist, MacArthur Fellow, winner of the 2003 John Burroughs Medal for nature writing, and president of the Blue Ocean Institute who was named by the Audubon Society as one of the hundred leading conservationists of the twentieth century — began to cry during his talk as he recounted a story of a bottlenose dolphin in the Gulf. Now, I’ve seen men cry and I’ve witnessed the occasional scientist expressing profound sadness, but seeing Dr. Safina’s seemingly uncalculated and public emotional response that arose from compassion was a first for me. In fact later in the talk, Safina explicitly referred to compassion as the most important quality we humans have to offer.

But it wasn’t this that kept tripping me up in my efforts to deepen my concentration around the breath. It was the story of the dolphin. Safina said:

I heard the most incredible story today when I was on the train coming here. A writer named Ted Williams called me. And he was asking me a couple of questions about what I saw, because he’s writing an article for Audubon magazine. He said that he had been in the Gulf a little while ago — like about a week ago — and a guy who had been a recreational fishing guide took him out to show him what’s going on. … he told Ted that on the last day he went out, a bottlenosed (sic) dolphin suddenly appeared next to the boat. And it was splattering oil out its blowhole. And he moved away because it was his last fishing trip, and he knew that the dolphins scare fish. So he moved away from it. Turned around a few minutes later, it was right next to the side of the boat again. He said that in 30 years of fishing he had never seen a dolphin do that. And he felt that — he felt that it was coming to ask for help.

Then he choked up, looked away from the audience momentarily, turned back to them and excused himself. “Sorry,” he said.

Dr. Safina, if you read this, please know that I thank you and think no apology is necessary.

Now, I’m a geologist, not a cetologist, so Dr. Safina’s story caused me to feel the need to do a bit of research on how bottlenose dolphins breathe. An article in Science told me that these athletic marine mammals show numerous physiologic adaptations to life in a dense, three-dimensional medium—that is, seawater—and as air breathers they are inseparably tied to the surface of the water. According to the website of the Dolphin Research Center, dolphins breathe air directly into their lungs via the blowhole, which is essentially a nostril that leads to two nasal passages beneath the skin. The blowhole is naturally closed and must be opened by contraction of a muscular flap. It opens briefly for a fast exhalation and inhalation. Air sacs under the blowhole help to close the blowhole.

Much to my amazement I learned also that dolphins are “conscious breathers” who must deliberately surface and open the blowhole to get air—that means they think about every breath they take; they concentrate on the breath. Bottlenose dolphins typically rise to the surface to breathe two to three times per minute although they can remain submerged for up to 20 minutes. How do they sleep, I wondered? Apparently, dolphins breathe while “half-asleep”; during the sleeping cycle, one brain hemisphere remains active in order to continue to handle surfacing and breathing behavior, while the other hemisphere shuts down. I tried to do my assignment, to focus on my breath, but I kept wondering if the recreational fishing guide to whom Safina referred had witnessed a dolphin, panicky, because it couldn’t breathe.

I’ve had asthma myself and have been through bouts of croup and asthma with my children. I know that suffocating feeling. I wondered if Corexit, the dispersant used to break up the oil in the Gulf, might affect the geophysical fluid properties of seawater so as to make breathing more labored for dolphins there. It’s been hard to find any information about this. Much of the bad news around Corexit relates to its geochemistry—not it’s physical, but its toxic chemical effects.

As many people know, seawater contains not only sodium chloride (ordinary table salt) but magnesium sulfate, magnesium chloride, and calcium carbonate which taken together as the “dissolved salts” in seawater are called “salinity.” It’s measured in parts per thousand (‰) which is equal to grams per kilogram. The salinity of freshwater is 0‰; normal seawater has a salinity of about 35‰. Salinity makes seawater very different from freshwater. Most animals have a specific range of salinities that they can tolerate partly because salinity, along with temperature, determines water density. Density and pressure are related to one another. In my research I’d read that dolphins can detect very small changes in pressure. Could a pressure sensitive organ such as a blowhole membrane be affected by changes in the chemical and physical properties of seawater?

I watched as Safina conducted a science demonstration on TED; he showed that dishwashing detergent (a dispersant) added to a glass of oil floating on water and stirred causes the oil to break up into small globules that remain suspended in the water. The water became cloudy, and I would bet that if I tried to measure the density and viscosity of the Corexit-induced mixture of oil and sea water, those parameters would have changed from what the dolphins are accustomed to for their voluntary breathing process. Does the changed physics and chemistry of Gulf seawater owing to Corexit-dispersed oil in the seawater affect the breathing experience of dolphins?

Since the blowhole is supposed to contract tightly to ensure complete closure when the dolphin dives, would oil dispersed in the water make the seal slippery and less secure? Could oily water get into a dolphins respiratory system? I’m sure that some scientists would say that these effects are “negligible” so I had to leave these questions to the cetologists.

I finished an unsatisfactory sit because I couldn’t easily receive the breath. My chest and heart felt heavy. I turned to one of our reading assignments for this month, This is Real and You are Completely Unprepared by “Zen Rabbi” Alan Lew, of blessed memory, who had been the spiritual leader of Congregation Beth Sholom in San Francisco as well as founder and director of Makor Or, the first meditation center connected to a synagogue in the U.S. Lew wrote:

We all share the same heart. We penetrate each other far more than we are ordinarily aware. Ordinarily we are taken in by the materialist myth of discrete being. We look like we are separate bodies. We look like we are discrete from one another. Physically we can see where one of us begins and another of us ends, but emotionally, spiritually, it simply isn’t this way. Our feelings and our spiritual impulses flow freely beyond the boundaries of the self, and this is something that each of us knows intuitively for a certainty (Lew 81).

Maybe Carl Safina’s heart ached because we all share the same heart. And perhaps I’m having trouble receiving the breath because we and the dolphins share the same lungs.