Listen! The Earth Breathes! November 8, 2012

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Anthropocene, climate change, earth system science, Ecozoic, environmentalism, global warming, Hurricane Sandy, hydrologic cycle, science, sea-level rise, Teilhard de Chardin.2 comments

This piece appears in Shambhala SunSpace.

Like many millions of people around the world, I was captivated by President Barack Obama’s election night victory speech. And my heart cheered when I heard the President say, “we want our children to live in an America that…. isn’t threatened by the destructive power of a warming planet.” Maybe the Earth has now, finally, made itself heard on the issue of the disastrous implications of global warming for all beings that live on this planet.

I’ve always favored scientist James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis that organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings on Earth to form a self-regulating complex system that contributes to maintaining conditions for life on the planet. And I’ve also been a big fan of Vice-President Gore’s book, An Inconvenient Truth, especially because he makes so clear that the Earth actually breathes. “It’s as if the entire Earth takes a big breath in and out once each year,” he wrote in referring to the Keeling Curve, the diagram by scientist Charles David Keeling that shows not only the overall increase in CO2 in the atmosphere starting in the late 1950s based on measurements of atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa, Hawaii but also the annual cycle of increase and decrease of CO2 in the atmosphere that results from the growth and decay of vegetation.

And now at the risk of committing the sin of anthropomorphism (attributing human motivation to an inanimate subject), I’ll suggest that Earth itself cast a vote in this election.

Some pundits say that “Superstorm Sandy” helped the President win the election partly because of his compassionate and competent response to the crisis. I’m no poll, so I don’t know. I hope only that this election marks our movement into a new geologic Era thatJesuit paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) once proposed: the Ecozoic, a new era of mutually enhancing human-earth relations.

In The Long Road Turns to Joy, Thich Nhat Hanh wrote:

You will be like the tree of life.

Your leaves, trunk, branches,

And the blossoms of your soul

Will be fresh and beautiful,

Once you enter the practice of

Earth Touching.

May the re-election of Barack Obama usher in the Ecozoic Era, a period in which we listen attentively to what the Earth tells us and live the understanding that we breathing humans are the breathing Earth.

Ocean as Carbon Sink January 9, 2010

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in climate change, earth cycles, hydrologic cycle.add a comment

Melting Glaciers December 10, 2009

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in climate change, geology, hydrologic cycle.add a comment

Though the New York Times chose not to publish it, I’m posting my letter to the editor regarding Thomas Friedman’s December 9, 2009 Op-Ed about ‘Climategate.’

To the editors,

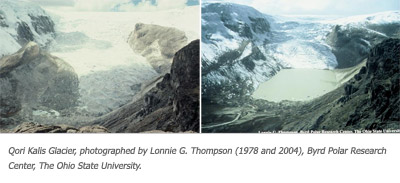

In “The Odds of Disaster,” (12/9/09) Thomas Friedman writes, “…evidence that our planet has been on a broad warming trend has been documented….” With the brouhaha about hacked data from East Anglia’s Climatic Unit looming over Copenhagen, I recommend the online archive of glacier photographs from the National Snow and Ice Data Center (http://nsidc.org/data/glacier_photo/index.html).

The collection contains photographs taken from the same vantage, at the same season, but separated by decades. Witness:

With regard to the Muir Glacier, according to U.S. Geological Survey scientists, the glacier retreated more than seven miles and thinned by 875 yards over a sixty year period.

One need not have a degree of any sort to see the melting. Whether or not anthropogenic greenhouse gases are the cause hardly matters; as the crysophere melts, meltwater expands, flows into oceans and sea level rises.

‘Climategate?’ I agree with Tom, “be serious.”

Jill S. Schneiderman

Professor of Earth Science, Vassar College

Poughkeepsie, NY

Image used by permission: NSIDC/WDC for Glaciology, Boulder, compiler. 2002, updated 2006. Glacier Photograph Collection.

Boulder, CO: National Snow and Ice Data Center/World Data Center for Glaciology. Digital media.

On Contemplative Times August 15, 2009

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in contemplative practice, earth cycles, hydrologic cycle.7 comments

A recent New York Times Op-Ed (August 14, 2009) contained the piece “Thirsting for Fountains.” According to the editors, they asked eight illustrators to observe for one hour the activity at a local water fountain. Their rationale: “If drinking fountains were as ubiquitous as fire hydrants, there would be no need for steel thermoses, plastic bottles or backpack canteens. Thirsty folks could just amble over to the next corner for a sip of free-of-charge, ecofriendly, delicious water.”

A recent New York Times Op-Ed (August 14, 2009) contained the piece “Thirsting for Fountains.” According to the editors, they asked eight illustrators to observe for one hour the activity at a local water fountain. Their rationale: “If drinking fountains were as ubiquitous as fire hydrants, there would be no need for steel thermoses, plastic bottles or backpack canteens. Thirsty folks could just amble over to the next corner for a sip of free-of-charge, ecofriendly, delicious water.”

I’m fresh off a week-long retreat on contemplative pedagogy sponsored by the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society so I am able to see clearly that the NYT editors challenged these illustrators with a contemplative exercise. Sit and behold. From what I can tell, the illustrators played to their strengths. All drew the fountain where they observed passersby. They made other observations: temperature and taste of the water; number, age, gender identity, garb, even species, of consumer. With words also, each painted a picture of activity at the fountain. What emerged was a cross-sectional slice of life. And the idea that a more harmonious and just means for human interaction with the hydrologic cycle as we attempt to procure drinking water is the fair and fluid one of fountains not bottles. Simple truth from a simple exercise.

Omega Institute Makes “Wastewater” an Oxymoron July 22, 2009

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in contemplative practice, hydrologic cycle.add a comment

This is cross-posted at Shambhala SunSpace.

Omega Institute’s Earth Dharma

By Jill S. Schneiderman

Department of Earth Science and Geography

Vassar College

Yesterday I went to the opening ceremony and ribbon cutting at the Omega Institute’s new Center for Sustainable Living (OCSL). Omega calls the Center a “Living Building,” an “Eco-Machine.” Essentially a wastewater treatment facility for the five million gallons of wastewater generated on the Omega campus each year, the Eco-Machine “closes the loop” on water use at Omega. Designed with the Hudson Valley’s ecological characteristics in mind, this building that is incidentally just up the Hudson River from Poughkeepsie, site of the nation’s first water filtration plant, produces all its own energy with renewable resources and captures and treats all its water.

As a result of the project, waste flushed down toilets on the Omega Campus flows into septic tanks where microbes begin to decompose it anaerobically (in the absence of oxygen). Then, water is pumped through two constructed “wetlands” where plants metabolize the waste and into two aerated ‘lagoons’ in a greenhouse, where plant roots suspended in the water provide surface area for bacteria to break down additional nutrients. Finally, the clarified water circulates through a sandy filter field where particulate matter and any remaining nutrients settle out. Single-celled and multicellular organisms including algae, fungi, bacteria, protozoans, zooplankton, invertebrates (e.g. snails) and vertebrates (e.g. fish) representing all the major groups of life are present in the Eco-Machine. The processed water is currently dispersed into groundwater but eventually will be reused to flush toilets and irrigate gardens.

OCSL’s Eco-Machine is remarkable, not only for closing the loop on water usage at Omega, but for producing all its own energy, controlling building temperature geothermally, utilizing solar and photovoltaic power, and collecting and utilizing rainwater. Additionally, it was built with materials made within a limited distance from the structure itself. Omega intends for it to be certified as the first “Living Building” in the United States. Regardless of whether the building achieves that official status, Omega’s construction project is not only consistent with the institute’s orientation towards holistic and sustainable living; it is a model for the present and future.

As a contemplative earth scientist, I love that Omega refers to its facility as an Eco-Machine. James Hutton, the 18th century Scottish physician and gentleman farmer, considered the founder of geology, derived a principle of an endlessly cycling “World Machine” and used it along with his belief in the existence of a benevolent God, to convince thinkers of his day that the Earth was ancient-millions of years old. The “paradox of the soil, ” he said, was that in order to sustain life, soil depleted by farming must have a mechanism to refresh itself, replenish depleted nutrients, and survive to grow crops once again. This cycle, he knew, would take time. And to his mind, a benevolent God would never craft an earth that did not have a mechanism by which to recycle itself. A closed loop of soil recycling, would take vast amounts of time-hence an ancient Earth-and would be an eternally cycling world machine that would forever sustain every living being. In Hutton’s most famous words the earth shows, “no vestige of a beginning, — no prospect of an end.” (Theory of the Earth, 1788, 304).

In his remarks at the OCSL’s opening, Robert ‘Skip’ Backus, the person who vision and effort helped bring the project to fruition spoke of the oxymoronic phrase ‘wastewater.’ Indeed, there is no such entity as wastewater and an understanding of another of the Earth System’s cycles, the hydrologic cycle, reveals this to be true.

In a continual cycle of condensation, precipitation, runoff, surface flow infiltration, subsurface flow, and evaporation, water circulates on and through the Earth-it is the original closed loop. Leaders at the Omega Institute have skillfully listened to the Earth and acted on what I like to think of as Earth Dharma-fundamental principles that show the path to right action in terms of abstaining from taking what is not given. Earth Dharma reveals how we, as one minute portion of the Earth System, should behave in light of our status as small but strong component of that System. I see Earth Dharma as a corollary to the first line of the Metta Sutra: “This is what should be done by all those who are skilled in goodness, and who know the path of peace.” The Earth is a storehouse of lessons consonant with the Buddha’s teachings. So it seems fitting to me that Omega has stepped forward once again to lead people in the direction of mindful living on Earth.

Jill S. Schneiderman is Professor of Earth Science at Vassar College. This year she received a Contemplative Practice Fellowship from the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. She is editor of and contributor to For the Rock Record: Geologists on Intelligent Design (University of California Press, 2009) and The Earth Around Us: Maintaining a Livable Planet (Westview Press, 2003).

Learn more about Omega’s Center for Sustainable Living here.

an Laffoley, marine ecologist and a vice chairman of the World Commission on Protected Areas at the International Union for Conservation of Nature, had an important op-ed in the New York Times on December 26, 2009 regarding the importance of the world’s oceans as sinks for carbon dioxide.

an Laffoley, marine ecologist and a vice chairman of the World Commission on Protected Areas at the International Union for Conservation of Nature, had an important op-ed in the New York Times on December 26, 2009 regarding the importance of the world’s oceans as sinks for carbon dioxide.