Not Standing Still: A Solstice-time Reflection from a “Geologian” December 21, 2012

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in contemplative practice, Ecozoic, environmentalism, geologian, meditation, mindfulness practice, science, Thomas Berry.Tags: environment, liberal arts college, lotus position, science

add a comment

This piece appears on the Shambhala SunSpace blog.

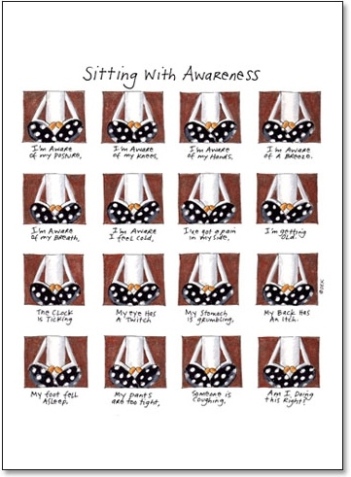

Among my favorite cartoons is one my mom gave me by the cartoonist and author of The Soul Support Book, Deb Koffman. Entitled “Sitting with Awareness,” in each of sixteen small square frames Koffman depicts a person sitting in lotus position wearing, what we call in my house “at–homes”– in other words sweatpants. (Click here to visit Koffman’s site — you’ll find the image under “Mindfulness Prints.”) Phrases beneath each frame taken together constitute the following poem. I sure can relate to it, and maybe you can too:

I’m aware of my posture, I’m aware of my knees, I’m aware of my hands, I’m aware of a breeze.

I’m aware of my breath, I’m aware I feel cold, I’ve got a pain in my side, I’m getting old.

The clock is ticking, my eye has a twitch, my stomach is grumbling, my back has an itch.

My foot fell asleep, my pants are too tight, someone is coughing, am I doing this right?

Why do I relate to this poem? Because as I pursue my work as a geoscientist–educator at a liberal arts college — reading, teaching, and striving at the intersections of earth science, gender studies, environmental studies, and history of science — I often wonder, “Am I doing this right?”

In answer to that question, I’m encouraged by news that The University of Virginia received a multimillion dollar gift this year to establish a Contemplative Sciences Center. One purpose of the center will be to promote awareness about the potential benefits of training one’s mind and body. David Germano, a professor of religious studies in the College of Arts and Sciences who will help lead the center commented, ”Hopefully, like drops in the ocean, this training can lead people to greater reflexivity, greater understanding, greater caring, greater efficiency and greater insight.” Huzzah to that.

This means greater validation for the kind of work I try to do as a contemplative educator in my science classes. Not that I doubt the benefits of contemplative practices in higher education. Students continue to write to me post-graduation, amidst real-life struggles about how the contemplative approaches I’ve taught them while they were in college have been among the most sustaining practices they’ve used to deal with everyday living. It’s just that professional scientific societies offer much advice about the fact that geoscientists — as educators and Eaarthlings — must involve ourselves in addressing “critical needs for the 21st century.”

For example, we are urged to prioritize efforts to ensure reliable energy supplies in an increasingly carbon-constrained world; provide sufficient supplies of water; sustain oceans, atmosphere, and space resources; manage waste to maintain a healthy environment; mitigate risk and build resilience from natural and human-made hazards; improve and build needed infrastructure that couples with and uses Earth resources while integrating new technologies; ensure reliable supplies of raw materials; inform the public and train the geosciences workforce to understand Earth processes and address these critical needs. It’s a long and lofty list.

But critically absent from the “critical needs” list are endeavors equally critical to achieving this balance on Earth. For example, for my personal list of critical needs as a science educator, I’ve added the following imperatives:

- Tell a scientific story of the universe that has a mythic, narrative dimension that elevates the story from a prosaic study of data to an inspiring spiritual vision;

- Articulate our dream of the future Ecozoic era, defined as that time when humans will be present to the Earth in a mutually enhancing manner;

- Circumvent the problem of anthropocentrism that is at the center of the devastation we are experiencing;

- Allow acknowledgment that currently, human beings are a devastating presence on the planet; supposedly acting for our own benefit, truthfully we are ruining the conditions for our health and survival as well as that of other living beings;

- Promote hope through contemplation of how tragic moments of disintegration over the past centuries were followed by hugely creative moments of regeneration;

- Recover the capacity for subjective communion with the Earth and identification with the cosmic-Earth-human process as a new mode of interdependence;

- Nourish awareness for a vision of Earth-human development that will allow a sustainable dynamic of the modern world;

- Foster development of intimacy with the natural world.

I developed this list as a result of reading the work of Thomas Berry (1914-2009), a leading scholar, cultural historian, and Catholic priest who spent fifty years writing about our relationship with the Earth. “The universe,” he said, “is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.” Berry, had a doctorate in history from The Catholic University of America, studied Chinese language and Chinese culture in China and learned Sanskrit for the study of India and the traditions of religion in India. One of his earliest books was a history of Buddhism. Having established the History of Religions program at Fordham University Berry published numerous prophetic books including The Dream of the Earth, The Great Work, and his last work The Sacred Universe: Earth, Spirituality, and Religion in the Twenty-First Century. This last writing especially fuels my conviction that science done well is also a spritual discipline. Berry called himself a “geologian” and wrote:

Our new acquaintance with the universe as an irreversible developmental process can be considered the most significant religious, spiritual, and scientific event since the emergence of the more complex civilizations some five thousand years ago…. if interpreted properly, the scientific venture could even be one of the most significant spiritual disciplines of these times. This task is particularly urgent, since our new mode of understanding is so powerful in its consequences for the very structure of the planet Earth. We must respond to its deepest spiritual content or else submit to the devastation that is before us (The Sacred Universe 119-120).

The notion that that my geology may be at once both scientific and spiritual has me also adopting the moniker, “geologian.” And that the University of Virginia is moving forward with its Contemplative Sciences Center fuels my hope that engaging science as a spiritual discipline in order to encourage embodied paths to wisdom and social transformation is in itself a worthwhile practice.

We’ve almost arrived at the winter solstice here in the northern hemisphere. On the year’s shortest day, the sun appears to halt in its progressive journey across the sky. From Earth it seems that the sun hardly changes its position on this day, hence the name solstice meaning ”sun stands still.” But despite appearances, the sun is changing its position relative to the Earth inasmuch as, speaking scientifically, the Earth circles the sun each year while it rotates on a tilted axis and creates the changing seasons (the hemisphere that faces the sun receives longer and more powerful exposure to sunlight). For half of each year the North Pole is tilted away from the sun and on the winter solstice the tilt makes the sun seem most faraway. This astronomical event announces the onset of winter in the northern hemisphere.

Speaking as a “geologian” I observe that these are indeed the darkest days of the year. But as I pause, as the sun seems to, at this point in my yearly journey around the sun, I note that in the darkness is the promise of the gradual return of more light. As you circle the sun and participate in the turning of the wheel of the year, what do you notice and to what do you bow?

Senator Rubio: Between Rock of Ages and a Hard Place December 4, 2012

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in geologic time.add a comment

Here is my unpublished Letter to the Editor of the New York Times in reference to NIcholas Wade’s piece on Senator Marco Rubio’s statement “I’m not a scientist.”

To the Science Times editor: