Against All Odds: A geologist revels in the unlikely reality of life on Earth November 4, 2016

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in book review, history of science, science.add a comment

This post reproduces a book review that I wrote for Science. (4 NOVEMBER 2016 • VOL 354 ISSUE 6312).

W hen esteemed geologist Walter Alvarez and his colleagues searched the lowlands of Eastern Mexico for ancient debris that had been ejected from the Chicxulub impact crater, they were following in the footsteps of renowned early-20th-century paleontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott. In his own time, Walcott wandered the Canadian Rockies seeking Cambrian-aged fossils that could shed light on this crucial time period when multicellular life began to flourish. As recounted in his obituary, “One of the most striking of Walcott’s faunal discoveries came at the end of the field season of 1909, when Mrs. Walcott’s horse slid in going down the trail and turned up a slab that at once attracted her husband’s attention. Here was a great treasure—wholly strange Crustacea of Middle Cambrian time…. Snow was even then falling, and the solving of the riddle had to be left to another season.” Serendipity combined with persistence eventually led Walcott to one of the most important discoveries in the history of geology—the softbodied fauna of the Burgess Shale.

In the case of the Alvarez group, two broken jeeps on the last day of the field season of 1991 nearly prevented the researchers from reaching the strange sand bed that Alvarez had chanced to read about in a book about the geology of the region published in 1936. As they “bounced along the rough road following the Arroyo el Mimbral, worrying as the Sun got lower in the sky,” they came upon a layer of glass spherules exposed in a steep bluff along the dry river bed. They suspected that the spherules were droplets of impact melt—“the most wonderful outcrop I have seen in five decades as a geologist,” writes Alvarez in his new book, A Most Improbable Journey: A Big History of Our Planet and Ourselves.

Alvarez is best known for helping to establish that a meteor struck the Yucatán, causing the mass extinction of half the genera of animals on Earth. In A Most Improbable Journey, he tells the story of the cosmos, Earth, life, and humanity using the interdisciplinary approach of Big History, which combines traditional historical scholarship with scientific insights. Alvarez aims to instill in his readers a sense of wonder that, despite enormous odds, there exists a planet (Earth) supremely suited for life. At the same time, he seeks to cultivate an expanded view of the nature of history, replete with contingency and consequent improbability, and to foster appreciation for the enormous stretches of time and space across which history has unfolded.

In each section of A Most Improbable Journey—“Cosmos,” “Earth,” “Life,” and “Humanity”—Alvarez uses both broad questions (have there been recognizable patterns, regularities, cycles, and contingencies in the history of continental motions?) and “little Big History” (how did the Spanish language come to dominate the Iberian Peninsula and then much of Latin America?) to help us comprehend “our whole situation.”

Throughout the book, Alvarez uses evocative phrases and images: History is “violent and chancy,” rocks “remember [their] history,” and mountains “are not wrecks—they are sculptures.” Compelling images of rock and architectural engravings, relief and sketch maps, and historical photographs and drawings enrich the discussion but, unfortunately, are not referred to directly in the text.

Alvarez invites his audience to read the book chapters in any order. Though I chose to read the book cover-to-cover, each chapter does indeed stand alone and therefore lends itself to this type of engagement. The book contains an appendix of resources that Alvarez annotates thoroughly, and it acts as an additional chapter that readers will likely enjoy perusing.

The paleontologist and historian of science Stephen Jay Gould wrote in an essay about the discovery of the Burgess Shale fauna, “So much of science proceeds by telling stories…. Even the most distant and abstract subjects, like the formation of the universe or the principles of evolution, fall within the bounds of necessary narrative” (1). In A Most Improbable Journey, Alvarez harnesses such narrative, enabling readers to experience the power of Big History.

REFERENCES 1. S.J. Gould,“Literary Bias on the Slippery Slope,” in Bully for Brontosaurus (Norton, 1992).

10.1126/science.aah5116

Artists for Soup in La Paz Centro October 1, 2016

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Uncategorized.add a comment

Here in La Paz Centro, Nicargua, at the Artists for Soup center, women in a biointensive gardening collective are growing food for their families, making art with their children, cooking with solar ovens they’ve made for themselves and networking with other Nicaraguan groups on resource issues and sustainability issues.

Augmented-Reality in Vassar’s Earth Science Program May 5, 2016

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Uncategorized.Tags: Augmented reality, Topography

1 comment so far

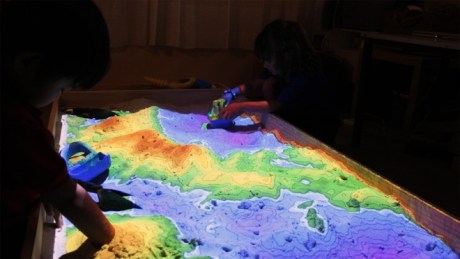

Developed by researchers at UC Davis, these augmented-reality sandboxes teach topography. Photo: Rhys George

It may seem a bit odd for a blog that aims to understand Earth’s truth to tout augmented reality when the actual reality of Earth has plenty to teach. Yet, here in the Earth Science program at Vassar we have an amazing new toy, an augmented-reality sandbox that enables us to mold a 4′ x 4′ box full of play-sand into valleys, mountains and craters. We can watch the transformation of the landscape in real time rather than over the course of millions of years. Our kinesthetic learners can develop landforms in which contour intervals change depending on the proximity of one line of elevation to the next.

And speaking of kinesthetic learners, for geology attracts many of us, check out Sir Ken Robinson’s TED Talk “How to escape education’s Death Valley.” …and come play in a sandbox!

The Elachistocene Epoch of the Chthulugene Period of the Ecozoic Era November 26, 2014

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Anthropocene, Chthulugene, Ecozoic, Elachistocene, Eremozoic, geologic time.add a comment

|

Era: Eremozoic or Ecozoic (after E.O. Wilson or Thomas Berry)

|

Period:

Chthulugene (after Donna Haraway) |

Epoch:

Elachistocene (Schneiderman 2014) |

If one accepts the idea that there is indeed convincing geological evidence for a new geological epoch (and I place myself in that camp) then there is obviously a need to name that epoch. However, geoscientists are not the only people who are entitled to challenge the proposed name and suggest alternatives. The history of science has shown that it is healthy for science to endure questioning about nomenclature from within and outside of the scientific community. I agree with those who critique the proposed term “Anthropocene” for using the species category in the Anthropocene narrative. Inequalities within the species are part of the fabric of the planetary environmental crisis and must be acknowledged in efforts to understand it.

Perhaps we should propose a name that is consistent with previous schemes of naming segments of the geologic time scale. Understanding the consistent semantics (as opposed to the inconsistent rationale for names of Periods of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic) is an important tool for settling on a name that achieves the purpose of acknowledging a new epoch while at the same time avoiding the pitfall of the homogenization all of humanity.

As many people know, the suffix –zoic means “life” thus, Paleozoic is ancient life, Mesozoic equates to middle life, and Cenozoic refers to new life. The epochs of the Periods of the Cenozoic Era are named to indicate the proportion of present-day (Holocene) organisms in the fossil record since the beginning of the Cenozoic era roughly 65 million years ago. Paleocene is derived from the Greek word palaios, meaning “ancient” or “old,” and kainos, meaning “new”; Eocene from eos meaning “dawn” of the new; Oligocene from oligos meaning “few” or “scanty” new; Miocene from meion meaning “less” new; Pliocene from pleion meaning “more” new; Pleistocene from pleistos meaning “most” new, and; Holocene from holos meaning “whole” or “entirely” new. Therefore, why not label the new epoch with a name that acknowledges the much less contested sixth extinction and increased diminishment of species on Earth in this epoch? What could we name such an epoch?

When I asked my colleague Rachel Friedman, a classicist, what would be the Greek for diminished amount of new life she explained that the antonym of pleistos (as in Pleistocene) would be elachistos and would be the prefix that might help me come up with a name that would acknowledge the diminished amount of species compared to the Holocene epoch. Though it isn’t the most elegant English, Elachistocene would mean “least amount of new” and I propose that name instead of Anthropocene for it adheres to the geological schema yet avoids the homogenization of humanity so problematic in the term Anthropocene.

Though I would make a friendly amendment to feminist scholar Donna Haraway’s suggestion to name the new epoch the Chthulucene (“subterranean born”) and propose Chthulugene as the name for the Period to which the Elachistocene belongs, might we take the opportunity of naming our new geological epoch to consider the designation of the Era as well? Theologian and scholar Thomas Berry wrote prolifically, pushing what he called “The Great Work” — the effort to carry out the transition from a period of devastation of the Earth to a period when living beings and the planet would coexist in a mutually beneficial manner; the result would be the erosion of the radical discontinuity between the human and the nonhuman. This vision of the Ecozoic stands in stark contrast to the notion of the Eremozoic Era imagined by renowned entomologist E. O. Wilson – the Age of Loneliness when other creatures are brushed aside or driven off the planet.

More Than Old Bones November 18, 2014

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Anthropocene, earth community, Ecozoic, geologian.add a comment

A recent Scientific American article published the remarkable image of a fossil of the early horse species Eurohippus messelensis unearthed from strata at a one-time site of oil-shale mining in Messel, Germany. Though well-known for the remarkable array of Eocene epoch (roughly 48 million years ago) organisms entombed in those strata, the early horse fossil standouts among the others; the fossil preserves the bones of a mare and her unborn foal (circled in the image above) in their correct pre-birth anatomical positions.

The find reminds me that fossils of extinct organisms are the remains of entires species, not just the bones of individuals. Each organism traversed an arc from birth to death and in the process reproduced members of its own species. Darwin helped human beings see this and evolutionary biologists and paleontologists that succeeded him have theorized the mechanisms that allow the reproduction of species. But this fossil makes visible reproductive capabilities of our more distant vertebrate ancestors. What’s more, the fossilization of a pregnant foal calls to mind the reality that, in the Anthropocene epoch marked by the sixth major mass extinction of life on this planet, human beings must admit the questionable ability of organisms living today to reproduce and survive extinction.

Jewish Farmers July 24, 2014

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Ecozoic, Eden Village Camp, environmentalism, Jewish spirituality, meditation, Rabbi Jeff Roth, Vegetarianism/veganism.add a comment

A recent article in the New York Times “New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm” spotlights some of my favoriate organizations in the Jewish social justice, environmentalism and spirituality movement. Pluralistic and conscious of differences of all sorts, it gives hope to me as a Jew during this difficult time. In particular I am proud to say that I’ve volunteered for three years at Eden Village Camp (mentioned in the article)

(Teaching Science at Eden Village, July 2011, photo by Meg Stewart)

and taken my Vassar students to Kibbutz Ketura on our March 2014 study trip. Note that althought Kibbutz Ketura is up to some interesting work, we also visited Kibbutz Lotan where there is some very interesting work going on in earth building and permaculture.

(Making bricks at Kibbutz Lotan)

I’ve also visited the Israel School of Herbal Medicine and spoken to rabbinical students on retreat at the Isabella Freedman retreat center. But i’d also like to add that the Institute for Jewish Spirituality, though not connected explicitly with Jewish agriculature and sustainability has been a thought leader in encouraging pluralism and spirituality among Jews. It’s an organization not to be missed. And I’ll also add the fact that I hope that in the future, students will come to Vassar as students to learn about Jewish environmentalism through our Jewish Studies and Earth Science programs with field work opportunities on the Vassar farm it’s CSA, the Poughkeepsie Farm Project, as well as nearby Eden Village Camp! Finally, a salute to Rabbi Jeff Roth who has been ahead of the curve on all of this. Check out his Awakened Heart Project!

Mary Anning: Google doodle celebrates the missing woman of geology May 22, 2014

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in feminism, gender, geology, history of science, science, women in science.Tags: Israel, Palestine, Study Trip, Vassar

add a comment

Google doodle celebrates fossil collector and paleontologist’s 215th birthday as reported in The Independent.

And since Google is celebrating Anning, whom I’ve always associated with ammonites, an extinct group of marine invertebrate animals (phylum: mollusca; class: cephelopoda), I’ve posted below a photograph of two of my students from our March 2014 study trip in which we visited the famous “Ammonite Wall” in the Negev Desert.

Pliny the Elder referred to these fossils as the “horns of Ammon” because their coiled shape was reminiscent of the ram’s horns worn by the Egyptian god Ammon. The photo below shows the remarkable exposure of a laterally extensive sedimentary layer chock full of ammonite fossils. That’s yours truly standing on the steeply dipping bedding plane.

And note the the great piece in The Guardian about Anning and the other lost women of geology.

One Earth Sangha January 22, 2014

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in 'Eaarth' Day, Anthropocene, Buddhist concepts, earth community.add a comment

The Earth as Witness:

International Dharma Teachers’ Statement on Climate Change

I learned of this initiative via a dharma talk podcasted from Spirit Rock. It is right up my alley and probably that of those of you who read this blog. I invite you to sign on.

Anthropocene Feminism November 18, 2013

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Uncategorized.6 comments

I’ve deliberately been keeping most of my thoughts to myself these days while marshalling my energy for a substantial writing project. But I’d like to make known an upcoming conference at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (April 2014) on Anthropocene Feminism. Of course, the Anthropocene is a topic of great interest to me and the notion that others are thinking about combining the two, as I like to do as well, excites me. I hope to submit a paper for the conference and perhaps bring students with me.

Think Fast, Live Slow August 30, 2013

Posted by Jill S. Schneiderman in Uncategorized.Tags: Contemplation, Geologic Time, Judaism

2 comments

This is a 13 minute video of a “TED-like” talk I was asked to give at a retreat for rabbinical and cantorial students from Hebrew Union College. I was asked to address the topic, “What do I know about transformation from my professional and personal life?” It’s entitled “Think Fast, Live Slow.”

August 2013, Isabella Freedman Retreat Center http://isabellafreedman.org/